Special shout out: My friend and colleague Adam, whose work at https://northomahahistory.com/ has inspired much of this blog, and whose groundbreaking work continues opening up new chapters of local history to new generations of readers

“I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.”

– John 8:12

“You are the light of the world. A town built on a hill cannot be hidden. Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. In the same way, let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven.”

– Matthew 5:14-16 (Sermon on the Mount)

“Some sentient power has wrought a marvelous change in the prairie lands in the span of year that measures a man’s life. Where the Indian’s council-fires burned in the days of Jackson, the Caucasian’s dream of beauty has found a fleeting shape in the white city that rises out on the plains today… At night, twenty thousand electric lights paint a scene from fairyland upon the waters of the lagoon. The temples that stand there are erected to appease the gods of the latter days, the gods of machinery, electricity, the liberal arts, and all their kith and kin.”

– William Allen White on Omaha’s Trans-Mississippi Exposition, 1898

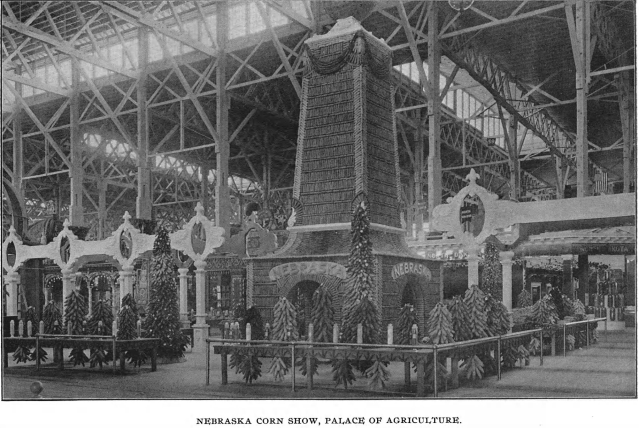

On a calm summer evening in 1898 there was electricity in the air, in the wiring, and flowing through the crowd of thousands gathered in silence around a lagoon in North Omaha, in darkness, waiting for the gods to reveal themselves. Neptune lit up first, surrounded by lily pads and water fountains that burst into brilliant flashes of “opals or rubies or sapphires or emeralds or diamonds,” according to one observer. Then an array of buildings lit up one by one, each representing various gods of capitalist industry: Manufacturing, Agriculture, Mines and Mining, Machinery and Electricity. The crowd stood in silent awe at the spectacle in front of them – many had never seen electrical lighting before that moment. Hovering just behind and high above Neptune, Lady Liberty held a torch “Enlightening the World,” illuminating truth, beauty, righteousness, all that was good and holy, including whiteness. She stood high above all the rest, perched atop the government building, christening the newly tamed West, surrounded by American flags.

Earlier that day, from the comfort of the White House, William McKinley pressed a button which shot an electrical current from the nation’s capital to Omaha, gateway of the West, carrying a message signifying the official start of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition. In his telegraph, McKinley congratulated the city and propped up the vast land between Omaha and Sacramento, as a whole, as a place of boundless potential. His message of hope and optimism resonated with an American population still reeling from the Panic of 1893, an economic crisis severe enough to challenge peoples’ faith in the United States, leaving many uncertain about their jobs, their banks, their government, their very futures. The electric signal from D.C., accompanied by the elaborate lighting ceremony, functioned like a magic trick, a political spectacle designed to instill faith in the future of the nation, its economy, its lifeblood.

The financial backers of the exposition hoped the spectacle would function as a defibrillator, presided over by the president and gods of industry themselves, to shock life back into the young city, and thus outward into the nation. From Omaha, at the heart of an expanding empire, pulsated the light of Western civilization to beam into the heavens and across the globe, spreading its benevolent touch to all who would submit to its iron, and often violent, will. White Christian settler colonialism had finalized its grip over the New World. From the first world’s fair in London half a century earlier, all that was worshipped inside the Crystal Palace had now crystallized all the way across the Atlantic, spreading across the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, the Great Basin Desert, and finally the Sierra Nevadas, to reach the Pacific. In his address on the Exposition’s opening day, prominent Council Bluffs businessman John Baldwin said, “the Exposition has become the instrument of civilization. Being a concomitant to empire, westward it takes its way… The Crystal Palace, the World’s Fair, The Trans-Mississippi Exposition.”

World fairs were opportunities for Western civilization to look at itself in the mirror, flex its muscles, ponder itself, explain and excuse itself, mostly to itself. All that technological and economic prowess appeared beautiful in the mirror, as did the exposition’s buildings and their statues, illuminated and reflected off the lagoon. This was the legacy left to us from the Greeks and Romans, and when the audience bore witness to the dark night suddenly turned into perfectly lit Corinthian columns, they stood breathless for a moment. To them it was magical, or supernatural, or some combination of both. A Harper’s Weekly writer stated, “I have seen men and women stand stupefied at the entrance of the Grand Curt, blinded as they would have been by a flash of lighting.”

Manifest Destiny was playing out right in front of their eyes, and they were honored to be a part of God’s plan to civilize the earth and its inhabitants, to rid the world of ignorance and evil. They were guests at the big party celebrating the end of the Wild West and the opening of a new era, in which life would be perfected, truth would be illuminated, and all that was righteous would win the day. The lighting ceremony at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition repeated every night throughout Summer and into Fall, each night leaving visitors in awe, feeling they were part of something holy, divine, eternal, transcendent.

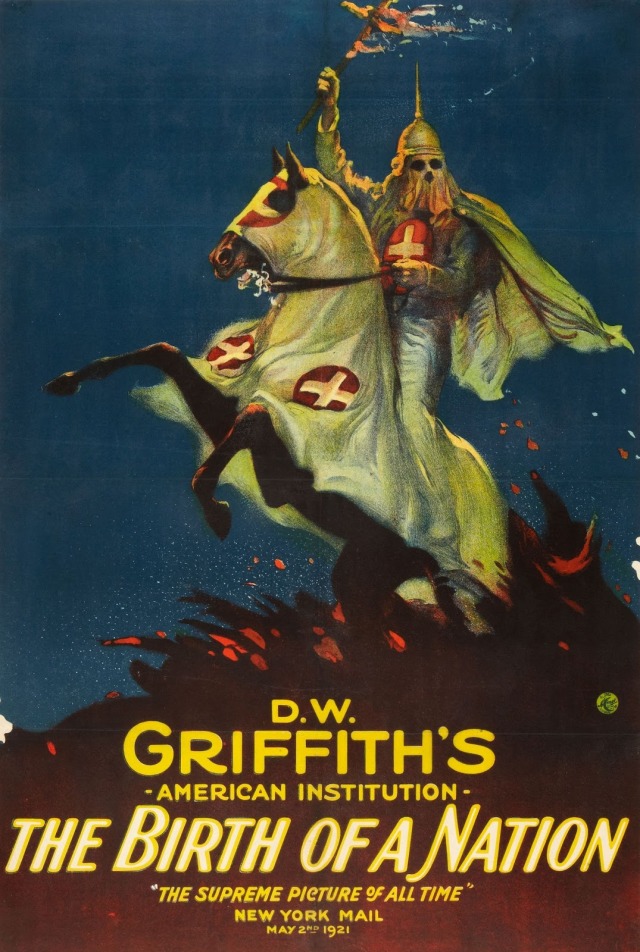

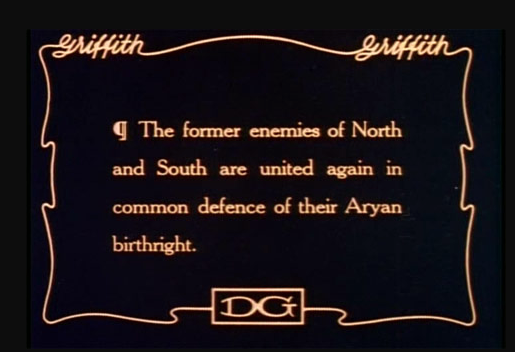

Of course, the reality was much different. The entire 180 acres of spectacle were a facade, a stage set designed to give the illusion of something greater. In his autobiography, actor Joseph Henabery, who played Abraham Lincoln in D.W. Griffith’s ‘The Birth of a Nation,’ recalled his time as a youth working construction for the Trans-Mississippi Exposition:

One big job was to dig a lagoon about six blocks long and three or four hundred feet wide. All the principal structures in the Exposition… were to be erected around the lagoon… Many of the buildings were of simulated marble in the classic style, with fluted columns. I watched the construction with great interest, especially the short cuts they used. Later on, I found that motion picture set construction was handled in much the same way. Of particular interest was the use of staff, a composition of plaster of Paris and hemp, cast in molds or formed by templates, on a backing of wire or burlap. When dry, the quickly formed staff material could be nailed in place in large sections.

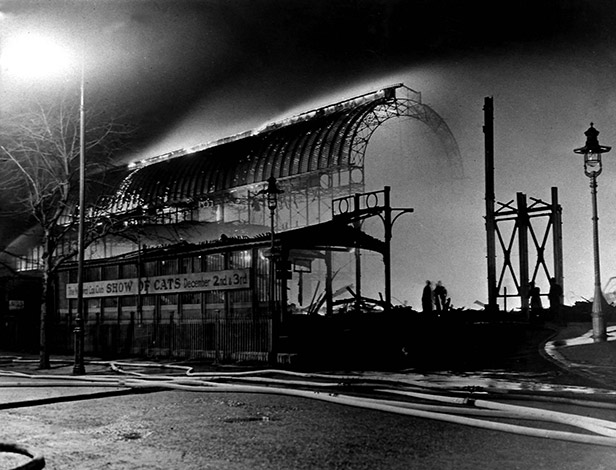

In other words, the great marble arches that recreated ancient Greece and Rome were actually made out of an artificial stone cast, and in just a couple years they would be crumbling into disrepair, then demolished shortly afterwards. The mesmerizing lights of Neptune, showering glittering jewel-water into the night sky, were nothing more than multicolored incandescent bulbs. Lady Liberty’s torch, which capped off the ceremony every night beaming a light of hope out into the heavens, was merely a high powered incandescent light which, along with the 20,000 other lights scattered through the lagoon area, was powered by a special plant built nearby. All of it was an elaborate stage set up to put on a mystical appearance. The audience would have been somewhat aware of the basic science behind the mechanisms at work, so while they didn’t view the stage set itself as being divine, there was a sense that all the inspiration behind these technological advances must have been guided by the hand of God, right into the laps of the white settler colonialists of the Great American West.

In October, in time before winter would have started wearing the faux Greek columns of the Omaha Exposition down, President McKinley made his grand entrance into Omaha as the keynote speaker for the ‘Peace Jubilee,’ a celebration of peace to mark the closing of a splendid little war against Spain over several foreign islands. The purpose of this event was more to justify war and imperialism than to celebrate peace, as many American citizens still viewed the whole expansionist endeavor with skepticism, and were speaking out against the prospect of a growing American empire, the eagle spreading its wings too far and wide. McKinley arrived by train to a raucous crowd, then pulled up to the Expo alongside Omaha’s movers and shakers in an elaborate parade event building up to his speech. Just three years before his assassination at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, McKinley stood in front of thousands in Omaha and defended his foreign policy with lofty rhetoric:

The faith of a Christian nation recognizes the hand of Almighty God in the ordeal through which we have passed. Divine favor seemed manifest everywhere. In fighting for humanity’s sake we have been signally blessed… The genius of the nation, its freedom, its wisdom, its humanity, its courage, its justice, favored by divine Providence, will make it equal to every task and the master of every emergency.

Here, McKinley invoked the image of manifest destiny and sent his message as clearly as he possibly could: the United States never fights wars for self interest, but rather for the sake of humanity and under God’s will, so anyone who questioned creeping American expansionism was going against God’s divine wishes, and who is anyone to question God? The speech was touted as a blueprint for Republican-led progress in expanding the American project into new heights heading into a new century, a way for the American people to move in unison towards a common goal, spreading the light of civilization to the world as the leaders of new industries and technologies. This would become the cornerstone of Teddy Roosevelt’s foreign policy only a short number of years later.

As the talons of America’s eagle reached out to grasp lands beyond its own shores, Americans attempted to process what, and who, had been taken into its grip over the past 50 years, as it finalized its control of its own mainland. They gazed upon the Native inhabitants of the mainland with titillated fascination. Who were these people whose lives had been so utterly shattered, upended, and reconfigured by Manifest Destiny? The Omaha Exposition promised to answer these questions for white settlers up close and personal, through the ‘Indian Congress,’ the last chance for the Indigenous peoples of the United States to be seen in their authentic state, before their way of life vanished completely. The official exposition guidebook called it, “the last opportunity of seeing the American Indian as a savage, for the Government work now in progress will lift the savage Indian into American citizenship before this generation passes into posterity.”

Representatives from two dozen tribes showed up to the ‘Congress,’ but their authentic ways of life were already essentially destroyed. The railroads had brought in floods of white settlers, who massacred the bison to near extinction, spread deadly diseases, and took the best land for themselves, relegating Indigenous peoples to the outskirts of what for thousands of years had been their own lands. In response, the prophet Wovoka spread the Ghost Dance Movement, which taught that Indigenous peoples would have their world once again, that a coming event would wipe out the white civilization that had been enveloping and swallowing their ways of life. They only needed to perform the Ghost Dance and everything would come back into the right place again. During the dance, many people went into a trance, or even lost consciousness and reported traveling to other worlds, speaking to dead relatives, seeing visions. They had come to believe all the dead ancestors would join them in a new world, free from the white man’s violence. It was a final desperate plea to the universe to stop the cultural genocide that had been occurring for the past few hundred years.

Lame Deer stated:

They told the people they could dance a new world into being. There would be landslides, earthquakes, and big winds. Hills would pile up on each other. The earth would roll up like a carpet with all the white man’s ugly things – the stinking new animals, sheep and pigs, the fences, the telegraph poles, the mines and factories. Underneath would be the wonderful old-new world as it had been before the white fat-takers came. …The white men will be rolled up, disappear, go back to their own continent.

The final thrust of this resistance ended in the Wounded Knee Massacre, in which paranoid white soldiers butchered several hundred men, women, and children as they camped along a creek in the winter of 1890. It was the end of an era, the end of Native autonomy as they had known it. As if to put a nail into the coffin of Indigenous resistance, the Omaha Expo featured a group of Arapaho and Cheyenne Ghost Dancers performing their ritual around an American flag, the embodiment of the white settler colonial project which had so thoroughly destroyed their ancient ways of life. In viewing this event, white spectators were therefore able to confirm their place as colonial masters over the West, the purveyors of all things considered civilized, and of that which would be thrown into the museum as archaic vestiges from a savage human past. Of course white people would cough up money to be able to feel like a part of this moment cementing whiteness as the big winners in the struggle over the American West. It was an easy sell.

Though deemed educational at first, in practice Indian Congress ended up becoming more like a Wild West show, with mock battles staged every day in which white and Native American people pretended to fight against one another. This novel concept was originally conceived by a fraternal group of well-to-do white men pretending to be Native Americans, called the Improved Order of Red Men, who proposed staging an epic battle: cowboys (white men) and ‘friendly Indians’ (played by white men in redface) vs ‘hostile Indians’ (actual Native American people). Although the ‘Order of Red Men’ might seem ridiculous today, they had membership of half a million at their height, including Presidents Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt, and Warren Harding, among their ranks. Apparently the irony, hurtfulness, and absolute absurdity of forming an all white group called the ‘Improved Order of Red Men’ that blatantly appropriated Native dress, language, and customs was lost on its members then, and continues to be lost on its members today.

Clown shoes aside, the mock battles were a huge success. For its opening day, 700 white and Native actors got into costume and acted out their battle, firing blank rounds, hooting and hollering in front the audience for full dramatic effect. As the battle raged, the villainous ‘hostile Indians’ acted out the scalping of their enemies and tying them to a post to burn them with the hot end of a stick, causing gasps from the captivated crowd. At the end of the massive theater production, the ‘U.S. Army’ came in to save the day, and the hostile Indians were forced off the stage onto a reservation. Each day the crowds were left as mesmerized as they were by the electrical lighting display each night. The play was a campy Greek tragedy, a kitschy re-telling of the Manifest Destiny narrative, in which brave westward pioneers, aided in part by the U.S. government, tamed the savage West through courage, sacrifice, determination, and the hand of God Himself.

The mock battles were a huge success for the Exposition’s organizers and their coffers. Many Indigenous people showed up on the promise they would be able to sell their wares to thousands of tourists, and many took full advantage of this opportunity. If they were to survive in the white man’s world, they would have to participate in his economy. Various tribal members camped out on exposition grounds in their traditional housing structures, including tipis and wigwams. Some chose to have their portraits taken by local photographer Frank Rinehart, in exchange for a copy of the photo. Rinehart’s collection from the Exposition is an invaluable documentation of the last generation of Native American people still living relatively immersed in the lifestyles of their ancestors. Through the camera lens, he humanized a people being dehumanized at every turn, and his compassion for his subjects comes through in the shots themselves, perhaps best exemplified in his photos of a strikingly beautiful Apache girl named Hattie. Her eyes tell the story of the last generation to live according to the old ways, and the first to enter a new era in which Native peoples would have to navigate new paths and new identities in a white world. If she were 15 at the time of the photos, she would have been just a baby as Geronimo led her people in one last stand against the U.S. military in 1886.

However humanizing Rinehart’s photos are, the Indian Congress as a whole was an ugly piece of white supremacist and nationalist propaganda, like every ‘living exhibit’ before and after it. On the opening day of the mock battle, there was a big parade which ended in an American flag raising ceremony, using the biggest flag that could be found, punctuated by a Native marching band playing the Star Spangled Banner. The symbolism was clear: these Natives had assimilated to the white ways, and no longer posed a threat to American progress. Geronimo and other Apaches were carted into the Exposition as prisoners of war, the old warrior of fierce reputation, who had eluded the U.S. military for many years, now available for autographs and photos, a novelty for white folks to gawk at.

Like Sitting Bull, Geronimo had become a legend and a caricature both at once, a man whose entire life story had been built on the theme of resistance, now withering in submission to the almighty white civilization which bulldozed through every crevice of the Americas. The writing was on the wall and Geronimo knew it. Defeated and forced to assimilate, he said,

“Right here at the exposition are enough people coming every day to put an end to every Indian in the world if they saw fit to do so. Then, besides this, the white men have all the guns, powder and bullets. They have all of the big guns and they are the ones that count…. I am an old man, and I want to see my people learn the ways of the whites. I want to see them raise corn and cattle and live in houses and I believe that the president and the big men at Washington will help my people if they will try to help themselves.”

Meanwhile, Native American kids were sent off to boarding schools to learn the ways of the whites, and in the process unlearn the ways of their families and ancestors. Teachers at places like the Carlisle school, where many Apache children ended up, cut these kids’ hair, gave them white names, converted them to Christianity, and many times abused them psychologically, physically, and sexually in the process. Near the twilight of his life, when Geronimo met with Teddy Roosevelt, he pleaded for the big man in Washington to allow his people to go back home to their home in Arizona. Roosevelt replied that Geronimo had a “bad heart,” that he had been a “bad Indian.” The president didn’t hide his racist views, stating, “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians, but I believe nine out of ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.” When the old Apache warrior finally died, newspapers ran headlines dehumanizing him and celebrating his death.

But Native American people were not the only ones exploited and dehumanized at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition of 1898. Organizers also imported set pieces from the South to recreate a Southern slave plantation, complete with Black actors playing the roles of enslaved African people, going about their daily business on the plantation. It was a bit of interactive theater, designed to allow white visitors to gaze upon and interact with the ‘enslaved people,’ or even touch them if one so desired. The idea was to show an exotic world of decades past, one people had only read about, and to show an authentic representation of Antebellum life. Advertised as a depiction of the “joys” of slavery, the Old Plantation also fell in line with a steady stream of ‘Lost Cause’ mythology seeping into the nation from the Southern states since the end of the Civil War. In order to push the narrative that slavery wasn’t really so bad after all, the Black actors were made to sing and dance while processing cotton, clearly marking the exhibit as a minstrel show under the guise of an anthropological study of enslaved African peoples.

Even children were employed in this racist, exploitative exhibit. The Nebraska State Journal reported:

In the old plantation is an interesting collection of plantation darkies. Ladies fond of children are especially pleased, as they find half a dozen small pickaninnies, about two years old. It is no uncommon thing to see three or four ladies with kodaks posing the children for a “snap shot” picture. The manager of the old plantation extends to the camera clubs the freedom of the old plantation for securing pictures. The old log cabins and peculiar people make most interesting subjects for the amateur photographer.

At the time, personal cameras were a new sensation, so the Old Plantation was an opportunity for people to take a snap, not unlike a turn of the century selfie, with ‘darkies’ dressed as slaves. These would be the main representations of Black people at the Omaha Expo, as well as at the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition three years later, where President McKinley met his fate from an anarchist’s bullet. And it was the unsettling sight of the Old Plantation exhibit in Buffalo, which followed in the footsteps of the one in Omaha, that led activist Mary Talbert to reach out to W.E.B. Du Bois and discuss ideas on how to combat such harmful stereotyping and exploitation. They then formed the Niagara Movement, precursor to the NAACP.

Although an organization called the Omaha Black Woman’s Club pushed organizers to employ local Black people in more prominent roles at the Expo, ones which would allow them to portray themselves as part of the larger Omaha community, and nation as a whole, their efforts were almost entirely fruitless. White managers made all the decisions, and they had little room for Black people in the Exposition except as caricatures designed to entertain the white masses. In the Expo’s Manufacturing Building, a Black woman dressed as Aunt Jemima served pancakes to white visitors, advertising the mix as a sort of ‘slave in a box’ that did all the labor of making pancake mix for you. Exploitation for profit was the name of the game.

However, there was another group of Black civil rights pioneers, ranging from conservative to radical and everything in between, who found a way to utilize the Exposition in a way that they felt would be beneficial. Omaha’s Ferdinand L. Barnett (not to be confused with his cousin Ferdinand Lee Barnett of Chicago, husband of Ida B. Wells), Reverend John Albert Williams, newspaper editor Cyrus Bell, politician Edwin R. Overall, and a slew of other local Black leaders aimed to create a public forum at the Exposition, featuring speeches by prominent white and Black intellectuals on various political topics. (Although women activists outnumbered men in this group, it was nonetheless headed by men.) They secured the Exposition’s main auditorium for the opening day of what they called the ‘Mixed Congress,’ in which race relations could be discussed and debated formally, in a structured manner, in front of an audience. Exposition organizers surely saw dollar signs with such an event, and hoped to draw in as many attendees from bordering states as possible, and surely also saw an opportunity to showcase Omaha as a tolerant, progressive city with its arms open to Black laborers who might seek to migrate from the South.

The official stated goals of the Mixed Congress were to “bring together representatives of both classes of American citizens for exchange of views on the industrial, educational, social and moral questions of vital moment to the prosperity of our country” and to “crystalize such views into some organization which will put into practice such principles as the congress may agree upon for the accomplishment of the end desired.” However political these goals may appear to be, Black leadership of the Mixed Congress explicitly stated the organization would “not be political, but ethical.” This was perhaps an attempt to draw in white participants who might otherwise be turned off at the prospect of getting into a heated, mud-slinging, political debate about difficult topics such as racial discrimination. It would also have served as a way to pitch the event as a nonpartisan one, in which people of all ideological stripes were welcome.

At the turn of the century, political partisanship was heavy indeed. The two most prominent Black intellectual leaders, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, and their legions of followers clashed over the politics of how to forge a more equitable and just future for their race. Where the conservative Washington advocated for a bottom up, incrementalist approach in which Black people slowly built their own equality through hard, steady work as individuals, the progressive Du Bois advocated for a full-scale top down approach, utilizing the power of the federal government to enact laws which would enforce equality at a structural level. Neither leader was invited to Omaha for the Mixed Congress.

Just a few years before the Omaha Exposition, at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Washington delivered his famous speech, dubbed the ‘Atlanta Compromise,’ advocating for Black people to steer away from political ideals that focused on structural racism and inequality, and to focus rather on building their own economic security, brick by brick, through trade work and menial labor. His was a bootstrap-mentality that demanded nothing from white people but patience, as Black folks respectfully found their way out of the deep hole they had been pushed into through centuries of oppression. In his Atlanta speech, Washington said:

The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing. No race that has anything to contribute to the markets of the world is long in any degree ostracized. It is important and right that all privileges of the law be ours, but it is vastly more important that we be prepared for the exercise of these privileges. The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house.

So where Washington and his ilk saw white people generally as friendly neighbors waiting for their Black peers to fix up their houses and curate their lawns, Du Bois saw them generally as antagonistic neighbors actively seeking to maintain a pristine, segregated, gated community, and to keep their Black peers out at any cost, by any means. On the topic of Black education and the value of pursuing white collar jobs, Du Bois said:

In the professions, college men are slowly but surely leavening the Negro church, are healing and preventing the devastations of disease, and beginning to furnish legal protection for the liberty and property of the toiling masses. All this is needful work. Who would do it if Negroes did not? How could Negroes do it if they were not trained carefully for it? If white people need colleges to furnish teachers, ministers, lawyers, and doctors, do black people need nothing of the sort?

Du Bois sought to form a phalanx of highly trained Black intellectual warriors to stand in opposition to the white power structure, to uproot white supremacy from its socio-political base, and knew just as well as Washington did that this process would be met with violent responses from whiteness. The major difference between the two men is that Du Bois was willing to lead Black Americans into this conflict and absorb white violence, and Washington was not. In many ways their story foreshadowed the ideological conflict between Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, although it’s important to note that by the 1960s, Washington’s ideas had been relegated to the dustbins of activist history, where King carried the torch of Du Bois to the very heights of the white power structure, and Malcolm X pushed the movement into new levels of radicalism almost unheard of a half century earlier. In other words, Du Bois helped set the standard of Black political activism that would carry on for decades after his death, even though at the time it was never clear this would be the case.

Both Washington and Du Bois’ calls for true equality were met with indignation and fury from white America, and perhaps not coincidentally, neither man was in attendance at the Mixed Congress. However, during the course of events leading up to the event, a war of words erupted in the public editorial pages of the Omaha World Herald between Reverend John Albert Williams of St. Phillip the Deacon, perhaps the most prominent Black leader in Omaha, and Reverend John Williams of St. Phillips of St. Barnabas, an Irish-American immigrant. The debate echoes that of Du Bois vs Washington, and arose following an editorial written by John Albert Williams, airing grievances about how Black people were often treated in Omaha, and offering solutions to help alleviate the problem. Williams stated:

It is rapidly becoming a notorious fact that it is almost a matter of impossibility for an Afro-American, however respectable or genteel he may be, to obtain accommodation in hotel, restaurant, ice cream parlor, labor shop or public resort of any kind. Certain places he is refused point blank. At other places he is met with some subterfuge or overcharged. Nor is this state of affairs confined to the city proper. It has invaded the great Trans-Mississippi and International exposition grounds.

Williams went on to list several examples of subtle and blatant discrimination in the Exposition as well as its host city, opining that business owners often choose to discriminate not based on their own personal prejudice, but based on the fear that white customers will stop frequenting their establishment if it’s known to serve Black people. He also noted that Black people from Omaha know which places discriminate, and would generally simply avoid them. But he questioned how visitors from out of town, especially during the Exposition, could possibly know which places to avoid, and asked if the city could afford to treat its visitors of color in such a way. As we so frequently do still to this day, Williams framed his anti-racist argument here in terms of economic health, which is often the best if not only way to persuade white people to take the issue seriously. Then he offered solutions to the problem, differentiating between legal and moral methodology:

The legal remedy is this: Taking advantage of the (Nebraska) civil rights bill, file information against, arrest and prosecute every person who violates this statute. Frequent lawsuits, fines and the attendant vexations and notoriety resulting there-from would eventually correct and modify, if not totally eradicate, the evil. This would create much unnecessary ill-will, which might otherwise be avoided. It is not the better plan, in my judgement…. must we seek this remedy?

The moral remedy is this: Believing in the injustice and iniquity of the pernicious public sentiment which fosters this discrimination injurious alike to the businessmen of our city and the people against whom they discriminate, let the liberal-minded and substantial white citizens issue a manifesto or statement over their signatures that they have no sympathy with such discrimination and that they will withdraw their patronage from all persons who practice it, and the evil will disappear…

…. it seems to me that this is the true way to right the matter. It will give the best results. It will avoid lawsuits and cheap notoriety. It will prevent ill-will and hard feeling between common citizens. It will remove embarrassment from the well-disposed proprietors as well as humiliation from those who would be their patrons and add to their business returns. It will give our city high rank as a progressive city among those of the land. It will above all show to the world that the metropolis of Nebraska believes in justice and right for all her citizens. Cannot this be done?

He then asked if “liberal-minded” city leaders would join him in the endeavor to lead the charge in publicly opposing discriminatory practices prevalent in Omaha, calling over a dozen of them by name in his closing paragraph, including the white Reverend John Williams, who would respond in due time. The concerns highlighted in this opinion piece were not called into question in subsequent responses, meaning people generally did not take issue with the concept that in spite of a state anti-discrimination law passed in Nebraska in 1885, racism was still alive and well, and practiced in relatively plain view, over a decade later. Cyrus Bell even did a bit of investigative journalism in order to detail this blatant discrimination, canvassing local businesses, asking what their practices were in regard to serving Black customers. Going door to door with blunt questions and an inquiring eye, he found clear evidence of widespread discrimination that proprietors would usually try to obfuscate through confusing, contradictory language games. Everyone discriminated in practice, yet none would freely admit it. Perhaps more importantly, very few white leaders were willing to publicly oppose it, as they were challenged to do.

In line with the confusing language documented by Bell, (white) Reverend John Williams responded to John Albert Williams’ piece by unleashing a tirade of gaslighting language:

The Rev. John Albert Williams makes a pathetic appeal in your columns for social justice and fair play toward his race… I wish his appeal could be not only heard, but answered as he desires; but he asks, I fear, for the impossible, so far as the world at large is concerned… I do not say that it will be forever impossible, but social equality between the different strata of either race… as man are at present, is all but a social impossibility. Of course, it is most gallingly impossible between the white and colored races.

Differences of education and external condition largely determine social rank and privilege between men of the same race among us. But no training or education, no external condition of wealth or culture can secure social equality or recognition for negroes. Among white men of any degree, educated or uneducated, the colored man may be nine-tenths white, and one-tenth black, and that one-tenth damns the nine-tenths of his Caucasian blood, however unexceptionable in education and training and gentlemanly bearing the man may be. He is barred by his fraction of black blood from equal association with the most uncultivated grade of white men.

He then claimed white people are not bothered being near Black people who are in positions of servitude and menial labor, such as porters, shoeshiners, and maids, but…

… as quickly as a colored man or woman… claims even the shadow of social equality then our proud white blood is up in arms, and we repel the contact with indignation at the presumption of the “n***er…” if he presumes to wear, or to ask for the shoulder strap of a lieutenant, or if he dares to sit at a lunch counter with us white men, or if he dares to ask for a soda at the same fountain with us, then our proud white blood is up, and the negro must be taught to keep his own place.

This is all… too sadly, unjustly true. No one knows better than Mr. Williams does, that I am absolutely at war with the social ostracism and injustice under which colored men labor. I detest our northern hypocrisy which arraigns southern men for their social injustice toward the black race, and yet without a hundredth part of the provocation makes constant use of the same, or similar injustice here. And yet, I can see no practical use in Mr. Williams or any of his people trying to force, by law or otherwise, social equality one day before white men are ready to grant it, as a natural inalienable right of every man, regardless of color. Colored men must labor and wait, must be self-respecting and patient, patient not in a humble or servile sense, but in a manly, independent way, which will prompt them to ask for no social favor that is not given them without sense of condescension on the part of those who yield them…

… Any other race with half the opportunities that colored men possess will forge ahead and receive the patronage of their own people. Why do not colored men do so, and let their civil rights under the law wait upon their natural and unquestioned right to do business for and with their own people, and with such others as would gladly recognize the force of character which will enable manly men to rise above their adverse circumstances? The mutual jealousies of the intelligent colored men of this city are far more detrimental to their common interests than the unreasonable prejudices of white men.

In Williams’ rollercoaster ride of contradictions, he simultaneously denounced anti-Black racism and indulged in it. In line with Washington, he said Black people need to simply pull themselves up by their own bootstraps and rise above the low-paying menial labor they found themselves bound to, and to simultaneously stop expecting white people to be ok with them doing that very thing. Using language such as, “our proud white blood” and “the negro must be taught to keep his own place,” Williams revealed his own white supremacist leanings, but then disowned white supremacy by claiming to be “at war” against racism. One might have asked Williams how he claimed to be at war against racism if his only solution was telling Black people to try harder and do better. His Black Anglican counterpart asked him to take the very first and most basic step in going to war against racism, which would be to clearly denounce racist practices by local businesses that were already illegal at the time, and instead of entering the battlefield, he ridiculed this call to arms as “pathetic” and unmanly. Of course, churches also operate as businesses to some degree, so it’s entirely possible Williams was trying to tow his white congregation’s line by assuring them he stood on their side of the color line, but anyone willing to cater this blatantly to racism is guilty of racism.

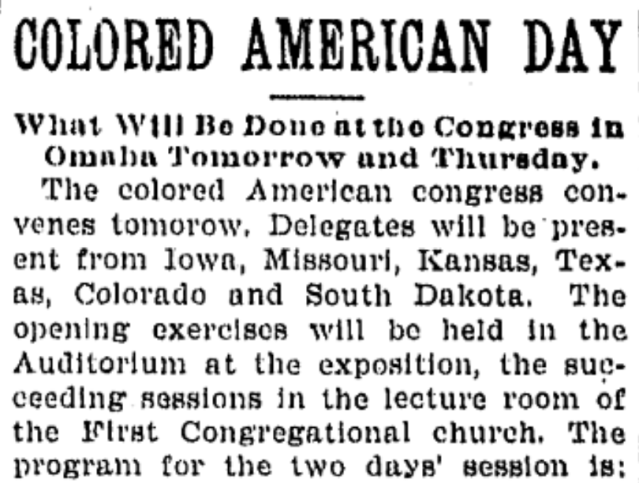

As the reverends Williams debated in the opinion pages of the local paper, preparations continued for the Mixed Congress, and the event ended up going off without a hitch. Judging by the war of words between local clergy, the decision to frame the event as somehow being apolitical might have been a wise one, if the goal was to keep tensions low. In order to demonstrate assimilation and respectability, the program consisted of patriotic songs along with speeches from an array of leaders from around the Midwest:

With its focus on peaceful, formalized dialogue about race and racism, the Mixed Congress represents an early effort on the part of community leaders to forge a path towards interracial unity, an idealism set in the midst of Jim Crow reality that was never truly confined to the South. While there appear to be no surviving minutes from the Congress detailing what exactly was said, the program clearly shows its creators were concerned with not only racism itself, but also how racism intersects with labor issues, and the media’s role in creating a more racially harmonious society. The care put into the program’s language indicates a high level of awareness regarding white fragility; the main question explored on the opening night of discussion wasn’t “how can racism be eradicated” or “how can racial equality be achieved,” but rather “what can be done to bring about a better and more respectful feeling between white and colored Americans,” followed by white and colored perspectives on the matter. If the editorial debate between the Reverends Williams represents the major ideological divide in the air at the time, then each side thought the other should do the heavy lifting in creating this ideal, sought-after feeling, bringing a tension which ironically would have led to worse and less respectful feelings between the two sides.

Again, there doesn’t appear to be any surviving records detailing the dialogues which occurred at the Mixed Congress, but on the topic of labor, it isn’t difficult to imagine speakers tackled the ongoing conflict between white unions and Black strikebreakers. White capitalists frequently pitted exploited, striking white unionists against Black strikebreakers seeking any sort of meager living they could find. While W.E.B. Dubois led the charge to push more Black people into academia, the arts, and white collar work that was primarily performed by the mind, rather than the body, the Black population remained disproportionately undereducated, politically and economically oppressed to the point of desperation, fighting for the scraps of whatever manual labor positions were still open after working class white American and European immigrant workers took the lion’s share. This often left Black workers in the position of accepting work with miserable conditions and extremely low pay, a phenomenon that left a bitter taste in the mouths of white unionists seeking better treatment for working class people.

In opposition to W.E.B. Dubois’ push to create more Black academics and artists, and in spite of the poor working conditions prevalent at the time, Booker T. Washington spoke in favor of Black industrial labor as the best strategy for paving the way towards a better future, and provided a model for Black vocational training schools with his increasingly famous Tuskegee Institute. Many influential white industrialists backed him in this vision, although their primary motivation was often to enhance their own economic standing, and that of their peers, rather than to uplift Black people. Washington found allies in practice, even if their motivations differed. Wealthy philanthropist George F. Peabody, namesake of the Peabody Awards who also served on the board of the Tuskegee Institute, said:

…. have you the least doubt that if one million Negroes, constituting nearly one-half of the men, women and children of Georgia were rightly educated to the development of their bodily health and strength and facilities and of the application of the same, which means their minds trained, to have their arms and legs work promptly and accurately in coordination, their moral apprehension rightly trained to know and do the right and avoid the wrong, and their affectional nature encourage to love and not hate their white neighbors, and to respect and honor their own sexual purity, that they would be worth in dollars and cents to the state of George more than three times their present value. If this be true, as I am positively sure that it is, and as the property of the State of Georgia is so largely owned by the white race, would not the gain to the white race, under present methods of distribution, be most incalculable in dollars and cents…

Also on the Tuskegee Board of Trustees, and an even closer friend of Washington’s, was another wealthy white man, William H. Baldwin, who cut his teeth in Omaha, rising up the ladder at Union Pacific Railroad. Baldwin originally came to Omaha on the invitation of his close friend’s father, Charles Francis Adams Jr., a Civil War veteran who was then president of Union Pacific. The year Baldwin arrived in Omaha, 1886, also happened to be the year of the Great Southwest Railroad Strike, in which railroad magnate and robber baron Jay Gould crushed the nation’s largest labor organization, the Knights of Labor, through the use of (often Black) strikebreakers and Pinkerton mercenaries, providing a model for how management could win future labor wars. While the Knights of Labor invited Black laborers into its fold, most unions after its dissolution were only open to white members, forcing Black workers into the desperate position of strike-breakers who felt they had no choice but to work for less.

Baldwin watched the politics of race and labor unfold from his office in Omaha, then traveled into the South to influence the politics of education and labor there. He was at the original meetings from 1898 to 1900 at Capon Springs, West Virginia, that led to the creation of the extremely influential Southern Education Board. As a close friend of Washington, Baldwin entrenched himself in the cause of public education for Southerners of all races based on the model of the Tuskegee Institute, aimed at vocational training to help grease the gears of industry and give people a steady living. While Baldwin claimed humanitarian motives for his efforts, W.E.B. Du Bois was skeptical, stating, “His plan was to train in the South two sets of workers, equally skilled, black and white, who could be used to offset each other and break the power of the trade unions.” Baldwin likely would have denied it, but his own words proved his true intentions were aimed at crushing unions so the U.S. would be able to compete with the cheap labor in other nations:

The union of white labor, well organized, will raise the wages beyond a reasonable point, and then the battle will be fought, and the Negro will be put in at a less wage, and the labor union will either have to come down in wages, or Negro labor will be employed. The last analysis is the employment of Negro labor in the various arts and trades of the South, but this will not be a clearly defined issue until your competition in the markets of the world will force you to compete with cheap labor in other countries…. I believe, as a last analysis, the strength of the South in its competition with other producing nations will lie in the labor of the now despised Negro, and that he is destined to continue to wait for that time.

Thus, while Booker T. Washington might have been helping Black people to some degree in the short term by providing a means to earn a meager living, he was ultimately playing into the hands of wealthy white capitalists who sought to exploit Black labor as strike breakers when the unions became powerful enough to force concessions through large scale strikes. W.E.B. Du Bois correctly surmised that white philanthropy was largely a scheme to further line the pockets of the white bourgeoisie, while producing public relations gold through generous donations to institutions such as the Tuskegee Institute. The titans of capitalism almost always had their way, skillfully playing working class people of differing races against one another, in order to keep them divided and powerless in the face of exploitation.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

On the same day corporatist President William McKinley spoke glowingly of American empire and the light of white Christian civilization in front of thousands in Omaha, a group of armed, mostly white, unionists of the United Mine Workers in Virden, Illinois, watched as a train of 50 Black strikebreakers and their families, over a hundred men, women, and children, rolled into town on a train car. The unionists had been at war against their employers for months, striking en masse until they could reach better working terms, and were fully aware of the strikebreakers coming into the area. The miners were led to action the previous year by General Alexander Bradley, who had learned to organize protest marches when Coxey’s Army of populists literally marched across the nation to Washington, D.C., demanding workers rights and human dignity for the poor and destitute during the economic depression of the early 1890s. The unionist men were organized into militias, armed and ready to fight to the death if need be, for a living wage. After a series of negotiations bore the fruit of an agreed upon wage for miners at the national level, the Chicago-Virden Mining Company stood alone in refusing to honor this wage, leading to a situation in which blood was sure to be spilled.

The Black strikebreakers were recruited from Birmingham, where company men told them the Virden miners had gone off to fight in the Spanish American War, so the Chicago-Virden Mining Company needed more labor. A previous group of their Birmingham peers brought up to Illinois, sensing trouble along the way, had refused to break the strike upon learning of the true nature of their trip. This time company owners were going to get their laborers into their mines and working, by any means necessary. From St. Louis, armed mercenaries of the Thiel Detective Agency boarded the train, in anticipation of the violence to come. The train doors were locked, keeping the Black laborers and their families trapped inside. The train depot itself had been fortified with a stockade, complete with barbed wire and sentry towers, inside of which were specially built company houses, a miniature community of exploited laborers sealed as if in a castle, from a potential siege. The stench of feudalism and backstabbing in the air, this group of Black laborers smelled trouble as well as their predecessors did, and there are reports that on this occasion, company men forced them to follow orders at gunpoint, making the situation a blatant case of kidnapping and false imprisonment.

As the train approached, a miner shot his rifle into the air, signaling to the other miners to prepare for the showdown. The train slowed to a stop as company men took position behind a long, narrow pile of coal they had stacked between the tracks and the stockade, armed with the cutting edge firearms of the day. Miners approached the scene armed with .22 caliber rifles and pistols, some without any firearms at all, and a shootout ensued, lasting roughly ten minutes. In the process dozens of men on each side were seriously injured and seven miners were killed, along with four company-hired men. It isn’t known for certain how many Black strikebreakers or members of their families were injured or killed, as there are no official reports on the matter.

What is certain is the company felt they needed state intervention to restore order and escort their workers into the mines safely, but Illinois Governor John Riley Tanner sided with the unionists. Tanner was clear in his judgement, bucking the longstanding trend of governors sending in state militias to aid capitalists in breaking strikes. He said, “The laboring man’s only property is the right to labor, which is as dear to him as the capitalist’s millions, and he has the same right to carry arms in defense of his property as the capitalist has to protect his millions.” Without support at the state level, company men persuaded the local sheriff to round up a citizens’ militia, asking for 100+ men, but only a dozen showed up willing to risk death for the company. Instead, a group of citizens sent a petition to Governor Tanner, stating:

“We are opposed to the importation of colored miners from the south under any and all conditions, as a menace to our peace and that of our city, believing, as we do, that it will depreciate the value of our property, foster crime within our midst, and degrade every social condition now existing in our city.”

Once again, the motivation for white citizens opposing the use of Black strikebreakers was racism and self-interest rather than humanitarianism. Regardless of motive, Illinois citizens were united against the company, giving the miners strength in numbers and ultimately, support from the state itself. Ahead of the shootout, Governor Tanner even sent company owner J.C. Loucks a letter warning that company leaders would be considered responsible for any potential violence in Virden:

After the gun fight, company manager Fred Lukins holed up in his house inside the protective cover of the stockade and fumed over Tanner’s refusal to send aid. He stated, “The blood of every man shed here is on the governor’s head. He is absolutely outside the law and has no justification whatever in refusing to send troops . . . His statement that the miner had the same right to fight for his property, which was his labor, as the mine owner did to protect his property, inspired these men to the action which they took in firing upon this train as soon as it came into our town.” Then Lukins took things a step further, doubling down on his company’s gamble that Tanner would eventually have to capitulate and send aid, puffing his chest about how tough he was by bragging that the sight of dead bodies didn’t bother him in the least, threatening to continue the fight regardless of how many bodies piled up in the process. This was perhaps not the public relations campaign the Chicago-Virden Mining Company needed, but it’s what they got.

In response, Tanner sent in state troops with gatling guns to restore order in defense of the miners, with the intent of restoring order and ultimately, punishing the company. A warrant was issued for Fred Lukin and two Thiel mercenaries, making it clear as day where all the pieces had fallen. Athough the charges were eventually dropped, the miners had done nothing less than set a new standard for labor rights movements moving into the 20th century. They stood their ground and proved they were willing to die for their cause, drawing sympathy from across the nation, and exposing their exploitative employers as ruthless tyrants hellbent on having things their own way, regardless of agreed upon, national level wages negotiated between labor and capital. In shooting at their labor force, the company shot itself in the foot.

In the meantime, the train full of Black workers from Birmingham and their families rolled on to Springfield, where they were left waiting to see what would happen to them next. According to the Illinois State Register, “Shivering and hungry in the third story of what is known as Allen’s hall are huddled together about 106 negroes, men, women and children, practically prisoners of war, and in danger of their lives if they should attempt to assert their liberty…” A couple of the men snuck out, only to be beaten into a bloody pulp by angry white mobs who didn’t want any more Black families moving into their town, especially as strikebreakers. Eventually these workers and their families received food and coffee, then headed back south, some migrating to St. Louis, others going all the way back home to Birmingham. They were, in essence, refugees in their own country. A decade later, Springfield would erupt into an orgy of violence as a mob of thousands of white people descended upon the Black part of town with torches, knives, guns, and bats, brutally slaughtering scores of people in the streets and burning their homes to the ground, sending the entire Black population fleeing from their own town, once again as refugees in their own country. In 1909, in direct response to this anti-Black pogrom in Springfield, and following the racist display of the Old Plantation in Omaha and Buffalo, W.E.B. Du Bois and and a group of multiracial activists first formed the NAACP, which would come to dominate the fight for justice and equality over the next several decades.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

With the rise of the NAACP and W.E.B. Du Bois as its bold, confrontational spearhead, in the face of repeated scenes of anti-Black violence such as the pogrom in Springfield, Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist ‘Atlanta Compromise’ philosophy began to crumble. White people were just not going to let Black people gain equality socially, politically, or economically. Only two years before the carnage in Springfield, Atlanta had its own turn in experiencing large scale communal anti-Black violence, in which a mob of thousands of white Atlantans savagely slaughtered innocent Black civilians, men and women alike, in the streets over several days, leaving roughly two dozen people dead. What could Washington say to this grotesque anti-Black violence… wait things out longer? Don’t use violence in self defense against violence? Herd yourself and your family into the slaughter? Go back to work, keep quiet about white supremacist terrorism threatening the very existence of Black people in the United States? In the waning years of his life, Washington and his ideas became increasingly irrelevant, as his optimistic view of white people was decimated and splattered across the streets of cities across the nation.

The Atlanta city government failed entirely to protect its own citizens during its pogrom, with Mayor Woodward on record saying, “The best way to prevent a race riot depends entirely upon the cause. If your inquiry has anything to do with the present situation in Atlanta then I would say the only remedy is to remove the cause. As long as the black brutes assault our white women, just so long will they be unceremoniously dealt with.” While city government failed miserably in stopping or even truly denouncing the massacre, the state sent troops in to ‘disarm’ every Black person in the city. They then rounded up about 300 Black men for questioning about their role in alleged attacks on city police officers. This pattern of allowing white supremacists to conduct pogroms in the streets of American cities in broad daylight, followed by sending in state or federal troops to disarm and police Black peoples’ response to the violence committed against them, would play out in cities across the nation throughout the Jim Crow period. Even Black professors were rounded up and shaken down, interrogated, blamed for their own oppression.

Here, the intersection of academic intellectualism and the “by any means necessary” strain of militant ideology famously espoused by the likes of Malcolm X and the Black Panthers a generation later come to light. One couldn’t so breezily dismiss armed Black citizens as ‘hoodlums’ when they had respected university professors in their midst. This concept so terrified the white establishment that it played a role in the original formation of the Bureau of Investigation, or BOI, later known as the FBI. Black militancy, headed by Black people who came to be called the ‘New Negros,’ ranged from those calling for using arms for simple self defense to radical separatists calling for the creation of a new Black nation state. Du Bois, for his part, an Atlantan to the bone, said of the Atlanta riots:

I rushed back from Alabama to Atlanta where my wife and six year old child were living. A mob had raged for days killing Negroes. I bought a Winchester double-barreled shotgun and two dozen rounds of shells filled with buckshot. If a white mob had stepped on the campus where I lived I would without hesitation have sprayed their guts over the grass.

Du Bois was not alone in his willingness to meet violence with violent self defense. Among the many budding Black intellectuals at the time of the Battle of Virden who would grow increasingly militant over the years was a young man from Omaha by the name of George Wells Parker. From an early age, Parker demonstrated remarkable talents as a thinker, writer, and orator. The son of a prominent Black businessman, he utilized the means at his disposal to curate his own personal library, accumulating 400 books by the age of 22. In a 1905 piece from the St. Louis Dispatch, Parker was described as a sort of tortured genius holed up in his dark room at 925 N. 27th St. (now the Viewhouse apartments adjacent to Creighton University), reading for hours on end, where he “mastered the Greek language unaided” and memorized passages of Huxley, Darwin, Comte, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Hume, Spinoza, John Stuart Mills, and other great thinkers. His book collection included “encyclopedias, works on science, literature, history, art and religion and many volumes of poetry.”

While Parker had his hands in a bit of everything, writing history appears to have been his true calling from early on. In 1898 while still in high school, Parker made his first splash as a promising public intellect at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition. The St. Louis Post article mentioned a diploma awarded to him, “for the best essay on Modern History, exhibited at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in 1898.” There does not appear to be surviving a record of this essay, but because the contest was open to students across the nation, it certainly was no small feat for young Parker to take first prize.

By the time he was of college age, Parker had already developed a devastatingly sharp tongue, piercing wit, and grace with language rarely matched by peers of his age. In 1903 he wrote a ‘defense of his race’ against an unnamed local newspaper editor who had written a racist diatribe claiming Black people shouldn’t be educated to seek socioeconomic equality, because it would damage the economic standing of white people, thereby disrupting the racial hierarchy. The editor suggested Black should people be content in their menial labor, lest they spark backlash from their white peers who would naturally defend their place at the top of that hierarchy. In the editor’s view, neither Du Bois’ nor Washington’s vision for a more equitable future would do, because even the most difficult and low paying industrial labor positions should be left for white men. Parker’s takedown reads like Mike Tyson swinging on Tucker Carlson in a boxing ring:

Under the caption, “The False Education of the Negro,” an Omaha paper published an editorial in the issue of December 3 which merits a criticism, and it is the purpose of the writer of this article to take upon himself the answering of that most unjust attack.

The color problem is the problem of the twentieth century. Nearly all of the great nations have this problem in some form or other and here in the United States the question is receiving its full discussion at the hands of persons both competent and incompetent, and if the views stated in the above mentioned article are the sincere expressions of this particular paper then it must of necessity be classed among the incompetent.

In the first place, the negro question in the United States is the result of a blunder. Some say the freeing of the slaves was that blunder; others argue that it was the enfranchisement of the freedmen; some lay it to the efforts to educate the black man; but if there were a blunder it was in all probability made by a Dutch Trader, who landed a score of Africans at Jamestown in 1619. The mistakes which have been made, the faults which have been discovered, the evils which have arisen, are all the consequences of that blunder and in the light of the twentieth century we find in America 10,000,000 of colored people struggling to attain the dignity of true manhood and true womanhood, and the man or paper that can see no virtue in this and can only find time to try to crush and humiliate this struggling mass not only commits a crime against these, but threatens the safety of themselves.

The paper referred to says: “No sane white man or white woman has at heart any real fear that social equality of the races will ever come about. The real thing which is objected to, and which is at hand is industrial equality.” That word “equality” has a very familiar sound. There are a few statesmen who had something to say about it in a declaration of rights, but their posterity have decided that they did not know what they were talking about.

The signers of that immortal paper did not mean that all men were socially nor morally equal, but what they evidently meant was that every man had a right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and the negro only asks that these inherent rights be his heritage as well as the heritage of any other race of beings. As to social equality, there are thousands of negroes in the United States who would be greatly humiliated to be classed as the equals of some of the types of white Americans.

But the industrial equality is a new battle cry. It has an ominous ring. A man can live without rights, but he cannot live without bread, and you who believe that the white man may oppress with impunity must not delude yourselves too long. If you attempt to force bread from the mouths of 10,000,000 people, I believe there are grounds for one to tremble for the oppressor. I do not mean by this that I am in favor of rebellion, but I do mean to say that history teaches that such a thing is possible.

I quote further: ‘The education has been generally lavished upon the negroes at the expense of the white – yes, doubly at their expense – for the education has turned menial servants into industrial equals and competitors.” What is education for but to uplift? Ignorance is the only crime and it is the ignorance in the world that makes the human lot so miserable. But ignorance is by no means confined to the negro, and if, in the future hundreds of years, the negro makes no more advance than that has been made by the whites in their thousands of years of freedom, then may they be left to the commiseration of the world. All men cannot work in “the fields and the railroad grades,” nor can all “young colored women do housework” for the whites. In a great country like America, where no law bids his son to follow in the footsteps of his father, I think that this should merit the condemnation of mankind if, after forty years of freedom, there were not some who longed to climb higher in the walks of life. And we, as a race, shall not pause to question if servility is our lot, for we know that it is not. We are men and manhood is not a question of color, but of character, and oppression is forging for this benighted race a character which shall not be spoiled, even in the face of such ignorant quibbling as was published in the newspaper referred to.

“The race problem,” says this Omaha paper, “reduced to plain English, is the servant problem. In freeing and educating the negroes we have made them our industrial equals and deprived ourselves of a distinctive race that had performed our menial work.” Why did not the paper say: “We should again make the negro a slave, for in freeing him we deprived ourselves of a class of good servants:” And then they say further that, “The situation came home in its full force when a crowd of striking union negroes fired upon a squad of white men who had taken their places. In leaping up to the industrial equality the negroes can ape the white man in more ways than one.” Then the negro unionists did wrong. But the white men strike too and shoot and kill, and yet the critic of the negro says that the negroes did wrong because they “aped” the white men. Then the boasted superiority of the whites lies in committing crimes which a colored man must not imitate. Then they are welcome to that kind of superiority.

The critic continues and speaks something about turning “savage into man,” and something about what “his half-made nature can comprehend.” I have often wondered which was the savage, the poor naked slave, cowering and weak, or the cruel white master, tearing the fallen man’s flesh with slave drivers’ help? Whether the patient black, toiling in the cotton fields, or the white man destroying his home, selling his sons, outraging his daughters and ruining his wife? Whether the young negro learning the alphabet by the dying embers, or the white man trying to keep him in perpetual darkness? Whether the negro, seeking the nobler walks of life, or the editor who would have him back in those days, where he probably supported his father in luxury and idleness?

Space will not permit me to say more. This must suffice until another time. But, in closing, let it be said that the writer is acquainted with many of the weaknesses of the negro, for he is of that race. The negro has his faults and his vices, but some of the worst are the teachings he learned while taking the 300-year course in the hard school of slavery. The white man is only reaping what it has sown. It was Burke who said that “it is sometimes as hard to persuade a slave to be a freeman as it is to persuade a freeman to be a slave.” It was hard at first for the negro to learn what it is to be free, but in the dawning light of this great century he begins to perceive the light; he begins to feel that he, too, is a child of nature and is destined to fill a part in the world’s great drama. And when you preach to him of treading the paths of slavery again you need only listen and you will hear murmurs of 10,000,000 hearts as they beat, Never! Never! Never!

Here, Parker demonstrated his early intellectual prowess and dexterity with language, masterfully breaking down his opponent’s argument piece by piece. The passages reveal a man far ahead of his time, writing about ideas that remain bitter points of contention to this day. The reference to Jamestown in 1619 foreshadowed the New York Time’s ‘1619 Project’ by over a century. His prose straddled the line between that of an armed, pro-Black militant nationalist and that of a nonviolent, New Testament Christian universalist. He alluded to armed Black rebellion against the racial apartheid state by referencing the historical track record of starving people turning against their oppressors, but cleverly dodged potential accusations that he was advocating for this sort of revolution by simply stating the fact that, “such a thing is possible.” The implied threat of revolution was reminiscent of Marcus Garvey, who at the time Parker wrote this piece in 1903 was still just a young man working at his godfather’s print shop in Jamaica. Parker also preceded MLK by six decades in stating that the measure of a man is in the content of his character, not the color of his skin, and anticipated Malcolm X’s classic line reversing the imagery of Plymouth Rock, having it landing on Black people, by reversing the image of who the true savage was, the “poor naked slave” or the “cruel white master” with the whip in his hand. In all these passages, Parker anticipated revolutions decades down the road.

The last paragraph in Parker’s 1903 piece also indicated the seeds of something larger looming over the horizon for Black Americans. In referencing the “dawning light of this great century” that illuminated the original humanity of Black people as “children of nature,” Parker reversed the overriding message of the Trans-Mississippi Exposition only five years earlier, and of every world’s fair since the Crystal Palace made its debut in London half a century before that. If the light of the new century was to be one that humanized and uplifted Black people, then it would necessarily humanize every other race of oppressed peoples living under the yoke of global white supremacy, including the Indigenous people put on display at the Omaha Exposition. Parker’s version of the “dawning light of the new century” reversed the notion of Manifest Destiny, reversed the idea that everything displayed at world fairs were celebrations of progress, rather than celebrations of racist barbarism against entire swaths of humanity. If Parker’s light was the true one, then the light of Western, Christian, European civilization was operating under a farce, because it was only by dehumanizing everyone else, after all, that white people were able to justify the entire white settler colonialist project in the first place. While Parker only briefly hinted at this new “light” concept which illuminated Black humanity in 1903, he was only just getting started on it, as we will see later.

Even with his radical ideas and sharp tongue, young George Wells Parker was willing to stomach, to some degree, the electoral politics of his day. During his college age years, he attempted to make practical change from within the system through the Republican Party, evidenced by his position as secretary of the Douglas County Colored Men’s Roosevelt and Webster Club. This group lobbied the Nebraska Republican establishment into political action which lived up to the ideals espoused by President Teddy Roosevelt when he said, “I cannot consent to take the position that the door of hope — the door of opportunity — is to be shut upon any man, no matter how worthy, purely upon the grounds of race or color.” Roosevelt had, after all, opened the doors of the White House to dine with Booker T. Washington, so perhaps there was cause for optimism in Washington’s idealist notion that white people would eventually accept Black equality, that their leaders would do what was right if only Black people didn’t act too brazenly.

In 1904, the Omaha Bee reported on the purpose and goals of Parker’s Roosevelt Club:

We view with apprehension and alarm the apparent growth of a public sentiment which is willing to acquiesce in state legislation having for its object the disenfranchisement of colored men, the passage of “Jim Crow” laws, the curtailment, if not the abolition, of public schools, and the practical reinstatement of the colored people in certain sections of the south. If the Republican Party of the state and of the nation will do its duty the wrongs and the injustice of which we complain can and will be remedied. In this fight for justice, for liberty, for the right and for fair play we want the Republican Party of Nebraska to be in the forefront of the battle.

By 1908 Parker was singing an entirely different tune. In another opinion piece written to the Omaha World Herald, Parker raged against the party he had believed in only four years earlier:

He is indeed a blind man who cannot see more nobility in a consistent and open enemy than in a treacherous and pretending friend… the republicans have joked so long with the negro they are unable to see anything but a joke…. The greatest harm done the negro was when the northern republicans went south and used the ignorant freedman agains the best interests of the south. These carpetbaggers sowed the wind and left the negro to reap the whirlwind… there are many among us who are going to work hard for (Democrat William Jennings) Bryan, and in so doing, if we gain nothing, we shall at least have the satisfaction of defeating or trying to defeat the party which we made, which we have kept in power, and which now in its days of prosperity has forgotten the hand which fed it.

What had happened in those four years that caused such a dramatic shift in Parker’s ideology? For one, he appears to have read up on some history, giving him a new perspective from the one he held in 1904. Only a month after his 1908 piece railing against the Republican party, Parker wrote another piece giving insight into his shifting worldview. In it, he quoted from a book titled, ‘Colonel Alexander K. McClure ‘s recollections of half a century:’

The disenfranchisement of the negro in the District of Columbia would be but the beginning of the end, as thereafter congress could make no accusation against the southern states for taking the same action…. The same republican authority, that had enfranchised the negro under the very shadow of the capital of the nation was compelled to declare that his disenfranchisement had become an imperious necessity to protect property and maintain social order. The southern states, which have, by ingenious constitutional devices, practically disenfranchised the negro, have simply followed the teaching of a republican congress and president, which disfranchised him in the capital city.

Parker referred here to the history of Washington D.C., which received an influx of newly emancipated Black people following the Civil War. In 1868 Black men residing in the District of Columbia were granted the right to vote, and in 1871 D.C. was granted self-rule as a territory. Its newly elected governor, Alexander ‘Boss’ Shepard, a Republican crony of President Grant’s, began a series of massive municipal projects that turned D.C. from a backwoods city along the Potomac into a proper national capital, employing thousands of Black workers in the process, who in turn provided their political support. Unfortunately, Shepard’s projects ended up running up a bill three times what he had asked and been approved for, leading to widespread and bipartisan opposition to not only his leadership, but also to the concept of D.C. as a self-governing territory. Usually a corrupt politician and his administration would simply be ousted, but in the case of D.C., Shepard’s rule came with the voting support of enfranchised Black men, which led to Congress taking the drastic measure of revoking D.C.’s territorial status, appointing a three member Board of Commissioners, effectively disenfranchising the entire city, regardless of race. This, Parker said, is evidence that the Republican Party would sell out Black people at any moment, and helped set the precedent for Jim Crow and the disenfranchisement of Black people across the South.

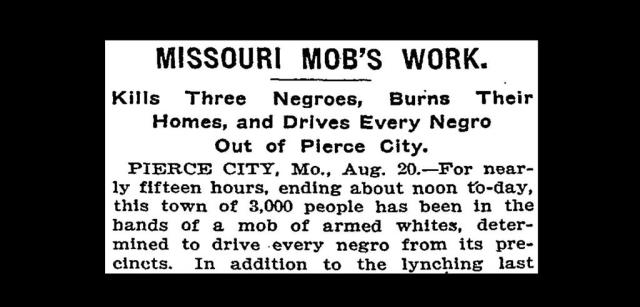

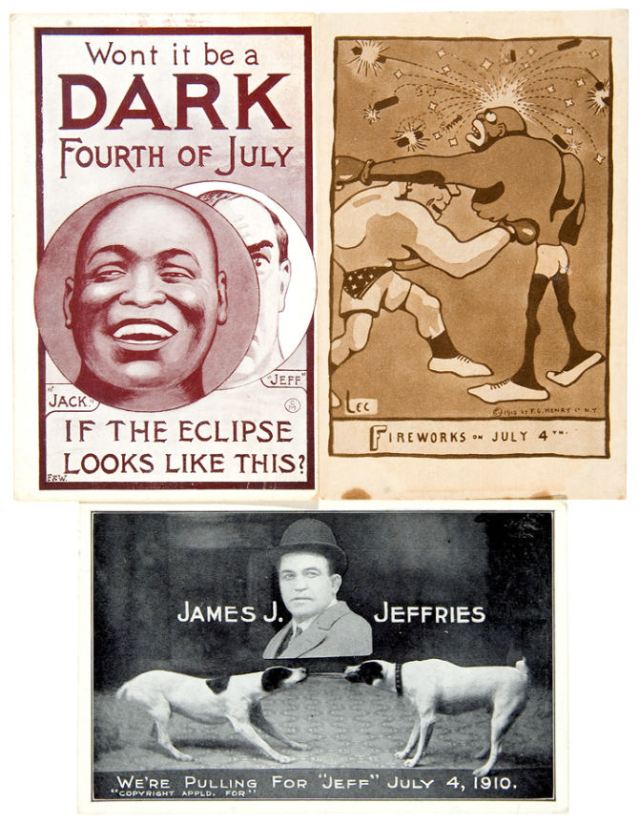

Parker’s argument is not without merit, and stands as a solid indictment against the Reconstruction era Republican party. Leadership starts at the top, and if D.C. represents the head of the nation’s political apparatus, then the most important progressive Republican politicians who claimed to champion the rights of emancipated Black people failed absolutely in their goal, right at the moment they were needed the most. Parker’s claim that it’s better to have a “consistent and open enemy” than a “treacherous and pretending friend” further anticipated Black nationalists such as Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X, the former of which famously met with the KKK in an effort to communicate about their shared desire to form racially segregated nations. At least they weren’t pretending *not* to be white supremacists, the thinking went.