Warning: Extreme anti-Black violence

Note: this piece focuses on some of the national context surrounding the lynching of Will Brown in 1919 Omaha, with a particular focus on race and racism in early 20th century United States. For an understanding of references made to the symbolism of the eagle, organ stops, and the Crystal Palace, please read The Lynching of Will Brown Part 2

“The way to right wrongs is to shine the light of truth upon them.”

-Ida B. Wells

Nestled along the Roanoke River just half an hour’s drive south of Lynchburg, Virginia, lies the Victorian-style house that is now home to the Avoca Museum. Not far from its greenish facade lies a tree stump, the last remnants of an old black walnut tree that served as the birthplace of lynching.

During the tense summer of 1780, under the shade of this historical yet mythological tree, renegade revolutionary judge Charles Lynch tied men loyal to the British crown up by their thumbs, strung them into the air, and gave them 39 lashes from a cat o’ nine tails. The lashes tore flesh from these men’s backs while Lynch forced them to utter the magic words, ‘Liberty Forever,’ the rallying cry of Patriots across the colonies. Afterwards, they were forced into signing up to fight against the empire they had been loyal to only moments before.

While these tactics might seem obviously reprehensible to us today, they were barely scandalous at the time. It was a time of war, after all, and Virginian Patriots had uncovered a Loyalist plot to sabotage lead mines used to produce revolutionary ammunition. Then-governor Thomas Jefferson had ordered Lynch to transport the worst offenders to Richmond for trial but Lynch refused, preferring his own brand of vigilante justice, an act of defiance for which he was never reprimanded -the Virginia General Assembly had made sure to pass legislation shielding the vigilantes from any prosecution, just as Lynch knew they would.

Thus, ‘Lynch Law,’ the extrajudicial practice of stringing people accused of crimes into the air as punishment, became synonymous with American vigilante justice during our very conception as a nation. Under the semi-watchful eyes of official authorities, this practice played out across the frontier and continues into present day. Whether we like to admit it or not, ‘lynch mobs,’ as they came to be known, are as American as apple pie. Thomas Jefferson himself, although he did not order it, also did not stop or condemn it.

Although people of all races and genders were lynched, Black men account for a vastly disproportionate amount of these atrocities, especially following the Civil War. And while not all lynching has revolved around the issue of race, Lynch himself used the term in relation to race as early as 1782, when he wrote, “I am convinc’d a Party 36 the first lynchers there is who by Lying has Deceiv’d some good men to Listen to them—they are mostly Torys & such as Sanders has given Lynchs Law too for Dealing with the negroes &c.”

From the Reconstruction period on, these events mainly served to maintain white supremacy by oppressing other groups, evidenced by the overwhelmingly disproportionate racial numbers found in every major study on the topic. Black men who were becoming too wealthy or powerful were viewed as threats to the traditional racial power structure, and lynchings were carried out largely to keep them from voting, seeking positions of power, or being too “uppity” (in other words, becoming financially successful.) The boot of whiteness had to keep the soul of Blackness in its subservient position at all costs, and then blamed Black people for their own suffering.

But lynchings also often played the role of entertainment, providing a sort of carnivalesque atmosphere that worked in tandem with the political functions they served. H.L. Mencken said, “lynching often takes the place of the merry-go-round, the theatre, the symphony orchestra, and other diversions common to larger communities.” Crowds of thousands would gather together, sometimes with newspapers advertising the event days in advance, providing ample time for entire families to travel from neighboring areas to be there for the big day. Vendors would arrive to sell food, drink, and chewing gum. Children often witnessed and participated in the macabre spectacle along with these throngs of adults. Photographers would show up and shoot the day’s proceedings. Mayors and sheriffs frequently put up no fight whatsoever to stop any of it, if they didn’t outright endorse it.

Sometimes death would be delivered swiftly, but that would ruin the entertainment value of the event. For maximum excitement, pleasure, and political impact, the torture and execution would often stretch over a period of several hours. Even after the body had taken in its last breath, the corpse could be further mutilated -burnt, broken, dismembered. In some instances, the bodies were dragged through Black neighborhoods in order to fully demonstrate the point, and in one case, a lynching victim’s severed head was thrown from a moving car at Black people walking down the street, a grenade of pure physical and psychological warfare.

Then these regular, all-American Toms and Susans would pose for a picture with their kill, like hunters do with their prey. Items would be taken from the carnage and kept as family heirlooms or sold as souvenirs, including pieces of rope, articles of clothing, body parts, and any weapons that were used. Then the photographs would be sold to postcard companies, who made fortunes re-selling the images of white supremacist Christian terrorists smiling, from ear to ear, over the corpses they so proudly annihilated. In the face of such bald-faced disrespect of the law, grand juries rarely convened, and those that did rarely found reason to dig very deep. The few indictments that arose would almost never lead to much, let alone guilty verdicts, and the still fewer guilty verdicts almost always led to pardons.

Such animalistic displays of pure, highly concentrated, premeditated violence and primal displays of racist dominance were then justified through an elaborate and sophisticated gaslighting process, whereby the supposed savagery inherent to Black people was cited as the very reason why it was morally necessary to carry out mob savagery against them. The ends could always justify the means, especially when it comes to protecting the white angel from the Black beast. South Carolina Senator Benjamin Tillman, speaking on the senate floor in 1900, claimed Black people and their progressive allies “wanted to put white necks under black heels and to get revenge” following slavery. He went on to say:

In my State there were 135,000 negro voters, or negroes of voting age, and some 90,000 or 95,000 white voters. General Canby set up a carpetbag government there and turned our State over to this majority. Now, I want to ask you, with a free vote and a fair count, how are you going to beat 135,000 by 95,000? How are you going to do it? You had set us an impossible task. You had handcuffed us and thrown away the key, and you propped your carpetbag negro government with bayonets. Whenever it was necessary to sustain the government you held it up by the Army.

Mr. President, I have not the facts and figures here, but I want the country to get the full view of the Southern side of this question and the justification for anything we did. We were sorry we had the necessity forced upon us, but we could not help it, and as white men we are not sorry for it, and we do not propose to apologize for anything we have done in connection with it. We took the government away from them in 1876. We did take it. If no other Senator has come here previous to this time who would acknowledge it, more is the pity. We have had no fraud in our elections in South Carolina since 1884. There has been no organized Republican party in the State.

We did not disfranchise the negroes until 1895. Then we had a constitutional convention convened which took the matter up calmly, deliberately, and avowedly with the purpose of disfranchising as many of them as we could under the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. We adopted the educational qualification as the only means left to us, and the negro is as contented and as prosperous and as well protected in South Carolina today as in any State of the Union south of the Potomac. He is not meddling with politics, for he found that the more he meddled with them the worse off he got. As to his “rights”—I will not discuss them now. We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will. We have never believed him to be equal to the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying his lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.

Here, Tillman might be credited for his honesty. The quote lays bare the true motivation behind ‘literacy tests’ at the polling booths, as well as the real overall sentiment among many white people regarding the prospect of Black equality. In this view, simply allowing Black people to participate in democracy represents the boot of tyranny over white people, indicating how frequently those who preach in support of democratic values are actually totalitarians hiding in democratic clothing. It also reveals the gaslighting mechanism at work, with the statement that the more Black people “meddled with” politics, the “worse off he got,” which might be compared to the timeless line, ‘I’m only hitting you because I love you.’

Tillman went so far as to state he would “willingly lead a mob in lynching a Negro who had committed an assault on a white woman” and counted at least 19 lynchings in South Carolina under his watch. Because of his willingness to state what so many white people thought and felt but were perhaps unwilling to say in public (Donald Trump?), the debate around lynching during this time frequently featured Tillman as a sought out voice in the matter. His views were thus normalized and validated through mainstream American society.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

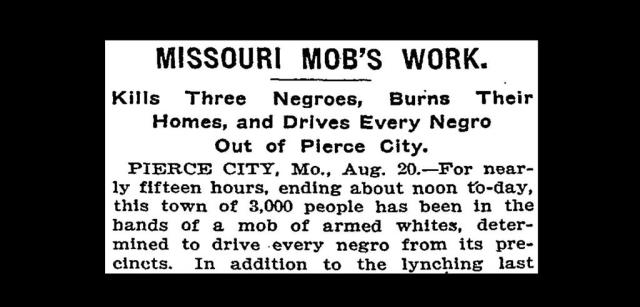

The mainstreaming of lynching played out in Pierce City, Missouri, in 1901, when a white woman named Gazelle Wild was found dead with her throat slit from ear to ear. In a frenzy, a white mob located a Black man they thought was guilty named Will Godley and promptly lynched him, after which they shot into his body many times over, accidentally injuring several of their own and killing a young white boy in the process. The mob supposedly also broke into the local Missouri National Guard armory (although it’s possible they were secretly granted access) and turned their sites on the Black section of town, where they shot Will’s grandfather French to death in his own home, and proceeded setting fire to Black houses and shooting at those fleeing for the trees, incinerating another elderly Black man in the process.

Will Godley was later discovered, as so many lynching victims were, to have been innocent.

The story out of Pierce City inspired Mark Twain to pen an essay called, ‘The United States of Lyncherdom,’ in which he takes aim at mob mentality and also gives credit to a handful of leaders who heroically prevented lynchings before they were able to occur. Fearing how white American society would react, assuming it was unprepared for his scathing words, he shelved the essay and it was only released in its redacted version following his death. The mob even had the power to silence the great, fearless wit Samuel Clemens.

While many white people shared Twain’s revulsion for the prospect of lynch mobs, those who were willing to speak openly on the topic, as the starting point for any dialogue, would often concede that they at least understood the reasoning behind the phenomenon, as a means of appearing the cool, rational centrist. In August of 1903, an article written by Supreme Court Associate Judge David J. Brewer appeared in Leslie’s Weekly and was carried by newspapers across the nation. Brewer argued in favor of abolishing appeals of criminal convictions entirely. Brewer stated:

Our government recently forwarded to Russia a petition in respect to alleged atrocities committed on the Jews. That government, as might have been expected, unwillingly to have its internal affairs a matter of consideration by other governments, declined to received the petition. If instead of so doing, it had replied that it would put a stop to all such atrocities when this government put a stop to lynchings, what could we have said?

It is well to look the matter fairly in the face. Many good men join in these uprisings, horrified at the atrocity of the crime and eager for swift and summary punishment. Of course they violate the law themselves, but rely on the public sentiment behind them for escape from punishment. Many of these lynchings are accompanied by the horrible barbarities of savage torture, and all that can be said in palliation is the atrocity of the offenses which led up to them. For a time they were confined largely to the south, but that section of the country no longer has a monopoly. The chief offense which causes those lynchings has been the assault of white women by colored men. No words can be found too strong to describe the atrocity of such a crime. It is no wonder that the community is excited. Men would disgrace their manhood if they were not. And if a few lynchings had put a stop to the offense, society might have condoned such breaches of its law; but the fact is, if we may credit the reports, the crime instead of diminishing is on the increase. The black beast (for only a beast would be guilty of such an offense) seems to be not deterred thereby.

What can be done to stay stay this epidemic of lynching? One thing is the establishment of a greater confidence in the summary and certain punishment of the criminal. Men are afraid of the law’s delays and the uncertainty of its results. Not that they doubt the integrity of the judges, but they know that the law abounds with technical rules and that appellate courts will often reverse a judgement of conviction for a disregard of such rules, notwithstanding a full belief in the guilt of the accused. If all were certain that the guilty ones would be promptly tried and punished the inducement to lynch would be largely taken away. In an address before the American Bar association at Detroit some years since, I advocated doing away with appeals in criminal cases. It did not meet the favor of the association, but I still believe in its wisdom.

Although Brewer was opposed to lynching, his widely published view was touted as a “good hard common sense” alternative between those who advocate lynching and those entirely opposed to it, in that it could potentially appease both sides of the debate. Therefore, a judge working for the Supreme Court of the United States argued in favor of negotiating with terrorists by abolishing criminal appeals courts altogether, and this view was spread throughout the nation as the reasonable middle ground between two extremes.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Meanwhile, the lynching continued.

Many of those fleeing the horror in Pierce City in 1901 ended up staying with friends or family 30 miles to the west in Joplin, Missouri, where in April of 1903, a young Black man named Thomas Gilyard was arrested on the accusation of killing a police officer. In a repeat of the events just across the way only two years earlier, the mob snatched Gilyard from his jail cell, strung him up and shot into his dead body repeatedly.

Then in June, a prominent Black teacher and community activist in Bellevue, Illinois, named David Wyatt found himself in an argument with the county superintendent, Charles Hertel, over the renewal of his teaching certificate. There are differing accounts of exactly why Hertel refused to renew the license, but Wyatt had been active in organizing Black people in the St. Louis area into political activism, something white authorities would certainly have been pressed on behind closed doors by groups of concerned white citizens.

At some point Wyatt reportedly shot Hertel and was immediately apprehended. Rumors quickly spread that the shot had been fatal, although it was not. According to J.J. M’auliffe of the St. Louis Dispatch, a mob formed around the jailhouse and, after some minor confrontation with local authorities, were granted access unopposed. The mayor had ordered police not to fire on them, but apparently it took leaders of the mob two hours to “break through several steel doors” in order to gain access to Wyatt, while officers “mingled” with them. In order to save face, local authorities would at least be able to say they didn’t hand over the keys directly.

The article continues:

… as he crouched in his cell pleading for mercy… his body was dragged by means of a rope tied around his neck through the principal streets… he was then hanged from a telegraph pole, his body mutilated and parts of the flesh distributed to the fiendish mob as mementos of its unbridled passion, and… his bleeding and torn body was burned…

It might have been assumed at the time, as it is so frequently assumed today, that the mob represented only the worst fringe elements of the town, but those assumptions have always been based on nothing more than faith. The evidence clearly indicates most people of the town either actively participated or sat back and watched as the mob leaders carried out the dirty work, and contributed to a code of silence when it came to holding anyone accountable in even the slightest ways for the crimes they committed in full view of police, and these people often photographed themselves smiling, posed at the murder site next to the murder victim, and carried body parts back to their homes to keep as family heirlooms for generations to come.

When M’auliffe starts probing local opinion on the lynching, he begins uncovering how this code of silence worked:

I was surprised to find that some men whose names are synonyms of good in the community feared to speak their minds. Still more was I surprised to find that the man who could call the grand jury is waiting for someone to request him to do so. And still more I was surprised to find that State’s Attorney Farmer had “nothing to say.”

Then he goes into some details about his interactions with the mayor:

The mayor’s position is this: He expresses the opinion that a community which would not be “stirred to fury and resentment” by the unprovoked shooting of its superintendent of public schools, ‘would not be made of desirable or the right stuff.’

The mayor says he does not wish to condone the action of the mob, but he can readily see how it was fed on the flames of prejudice through a “negro agitator who has been busy in Belleville under the equal rights act.”

Then the feisty reporter set his sights on Circuit Judge R.D.W. Holder, who was spotted at the public square an hour before the lynching.

Asked about the circumstances around the lynching, Holder said, “I do not know much about it… except what I have hear. Yes, I read the accounts in the St. Louis and Chicago papers.”

Asked about his opinion on the lynching, he said, “I have no opinion; a judge cannot have one. I am glad I know so little about it as I do.”

Pressed on the matter, reminded a lynching had in fact occurred in his county and that some of the best citizens openly oppose lynching, he said, “I am willing to admit as much. The people of this city believe in the law; nothing in the entire history of Belleville shows anything similar to what has happened. Lynchings are bad things.”

Asked about calling a special session for a grand jury, he responded, “I have received no request to do so.”

Asked if he could convene a grand jury upon his personal request, he said, “I could, but I would not care to do so at this time… It would be hard on many of our farmers to ask them to leave their work now and the expense to the county would be considerable.”

Finally, when M’auliffe approached local businessmen, one of them said, “Please do not ask my opinion. I am not bothered about it at all. I have enough to do to look after my own business.”

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

It is difficult to ascertain the true convictions of these prominent locals, since they appear to have either been truly confused, simply terrified, or some combination of both. The fact that a news reporter was so breezily able to get a circuit judge to say “I have no opinion” on lynching and “lynchings are bad things” almost within a single moment seems to demonstrate an overriding fear which led to confusion, either feigned or authentic, when it came time to make some sort of moral judgement about the matter.

Feeling the same pressure as Mark Twain and perhaps with similar views, only without the privilege to have their thoughts written down and placed in a message in a bottle for posthumous discovery, the civilized white men of the heartland of America stumbled through answers on even the most basic questions regarding absolute human depravity. The entire series of verbal diarrhea vomiting from these authority figures’ mouths reminds one of the questions posed by the 1946 trials in Nuremberg and the questions following the Stanford Prison Experiment a few decades later. Autopsies on the physical remains of human victims are straight forward enough, but autopsies on the corpses of basic social decency are another task altogether.

Regardless of the complex questions lynching and similar phenomena pose, one thing can be certain: whatever the adults are doing in town, through it all, children are always watching.

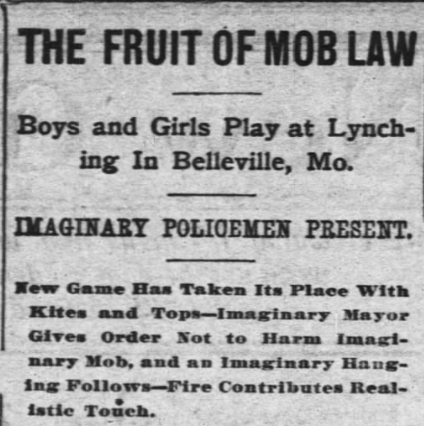

Another St. Louis Dispatch journalist wrote of his trip to Belleville, Missouri (part of Joplin) following the lynching of David Wyatt, and painted a grim picture of just how normalized lynching truly was. This report told of a new game, the “game of lynching” which “for the time being has eroded out baseball and jackstones, being vastly more exciting, and, if continued until fall, promises to deprive of some of its prestige the game of football.”

The journalist spared no detail in their description of this new game:

The children of the town, deducing from the light and airy manner in which many of their elders refer to the lynching of the negro Wyatt on the public square that the game is a proper and creditable one and deriving from the studied inactivity of the authorities the assurance that it is perfectly safe, have entered into the game with zest, and many of them have become adept at it.

If the game takes its place on the year’s calendar of sports and “lynching time” recurs with the same regularity as “kite time” and “top time” the children will by the time they are grown by quite facile as lynchers.

The game starts with the intended victim, generally a boy, crossing in the weeds in a make believe cell in an imaginary jail. The lynchers, boys and girls, gather under the nearest electric light and vow with great ferocity that “the n****r must die.”

With shouts as hoarse as they can make them the youngsters make a rush for the make believe jail and dance about it with an imitation of fury even more realistic than that of the crowd which surrounded the Belleville jail a few weeks ago.

Make believe policemen hang about, but make no attempt to disperse the mob.

A make believe mayor makes a speech studded with terrible adjectives, immediately following which a rush is made and the make believe front door of the imaginary jail is broken in. The mob is driven back by an imaginary force of defenders. The desperate mob withdraws a pace and confers.

The consensus of opinion is that the bastille can’t be taken because the defenders have weapons filled with injurious bullets, and they are all agreed that, while they are bent on killing the prisoner, they don’t want to run any risk in doing so.

Some try to convince the others that the authorities are their friends and would not harm them for the world, but still they hesitate. After an imaginary wait of several hours a bold spirit creeps close up under the walls of the jail and comes running back in great joy.

“It’s all right, feller!” he shouts. “They mayor has given orders to the guards that they are not to hurt us. Our revenge is at hand.”

They shout hoarsely and again rush upon the jail. The guards are locked in the imaginary office and the back door is not defended. They break it in with imaginary sledge hammers, and in a little while the victim is pounced upon and dragged down the imaginary steps and out on the street.

Emulating the real mob, they are not content merely to take him to a telegraph pole and complete the imaginary hanging. They pull and haul him over the sidewalk and street, shouting merrily the while. It is such fun that by this time they have forgotten to be fierce.

Finally the victim is pronounced dead, and a piece of paper is set on fire to give the proper realism to the finish.

Then they imagine it is the next day, and the leaders go around imaginary street corners telling what part they took in the make believe lynching.

The game ends with the make believe authorities reposing on a nearby lawn, complaining that they cannot ascertain the name of the lynchers and languidly announcing that they will call the attention of the grand jury to the lynching next year.

The cycle of lynching therefore played back into itself, a positive feedback loop that helped white Americans define themselves through the ritualistic act, through the telling and re-telling of the lynching narrative, to the point that each individual lynching followed the same typical plot line. The reporter called it a ‘game’ but the more accurate label would be ‘theater,’ as there was no competition or goals by which players of the game might win or lose. Rather, these kids took on characters playing sacred roles they viewed as being vital for the protection of their society from the forces of evil and savagery. They were preparing themselves for the real thing, and a child of five in 1903 would have been 20 years old in 1919, the year Will Brown was mutilated in the streets of Omaha, as so many Black people were in the streets of cities across the nation.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

In 1903, as kids trained themselves in white supremacist terrorism through play, and prominent adults debated the morality of this terrorism, the triumphs of western civilization, global capitalism, and white supremacy continued brewing in the meticulous planning of more world’s fairs.

On the same day that Justice Brewer’s centrist views on lynching spread across the nation, another big story ran by its side: the next offspring of the Crystal Palace would sprout from the same soil that David Wyatt’s body had recently returned to, as Missouri would host the next world’s fair in 1904.

The artwork for the fair was handled by Czech painter Alphonse Mucha, whose specialty was depicting beautiful, pure yet sensual women in the style of Art Nouveau. The poster depicts a calm, regal, lily white woman who might be thought to represent Lady Columbia, or the ancient Roman goddess of Liberty that now stood to represent white, Christian, enlightened Western Civilization seated next to the gears of technology that pushed whiteness closer to godhood, separating it from the savage state of humankind in its primitive form. Behind her, a docile Native American man reaches his arm around her, yet he is no longer a threat. His face is defeated, his eyes gloomy, and his hand is embraced by Lady Liberty warmly – she is in control, and the final culmination of Manifest Destiny, the ideals pushed forth at the Crystal Palace, have successfully spread across the Great Plains to the West Coast, enveloping the New World in total dominance.

Vulcan, the Roman god of fire, volcanoes, the forge and metallurgy, made his appearance at the fair in the form of a colossal iron ore statue, which remains the largest cast iron statue in the world. Vulcan is one of the oldest Roman gods, dating back to the Etruscan period, who survived in some form through Greek and Roman civilization and continued his presence through to the American empire. In ancient Rome, he was celebrated for creating weapons, armor, and jewelry for the other gods. Every year on August 23rd, when crops were dry and at most risk for catching on fire, festivals called Vulcanalia were held in honor of the fire god. In these festivals, Romans threw animal sacrifices into massive bonfires, which were meant to placate Vulcan so he wouldn’t lay down his wrath upon Roman crops, cities, and citizens.

In our desperate attempts to control nature, humans created ritualistic cleansing festivals in the hope that civilization would not crumble. When Rome burned in the Great Fire of 64 c.e., many placed blame on Nero, many on Vulcan. When Mount Vesuvius erupted only 15 years later, vulcan’s wrath showed its full power by destroying Pompeii entirely. Civilization is a fragile thing, so humans must perform sacrificial rituals in order to keep it afloat.

Many American lynchings involved fires and burning of corpses, or sometimes burning men alive. When Ell Persons, an elderly Black man in Memphis, was accused of raping and decapitating a 15 year old white girl in 1917, a lynch mob formed and burned him alive on a bridge over the Wolf River. Afterwards, his remains were scattered down Beale Street, a predominantly Black neighborhood. It was Person’s head which served as the projectile launched at Black people walking down the street.

Person’s ‘trial’ revolved around the absurd claim that his image was imprinted into the eyes of the young girl’s corpse, an idea sprouted from pseudoscience gaining traction at the time, under the guise of biometrics.

In another 1917 incident in Waco, Texas, a Black 17 year old named Jesse Washington was accused of murdering a white woman and a kangaroo court quickly formed. He confessed to the crime and was taken by a mob on is way out of the courthouse. The mob beat him and tied a chain around his neck. In front 15,000 people, including children, they doused him in oil, castrated him, and cut off his fingers and toes. Then they started a fire, hoisted him to a tree so he dangled above the flames, and repeatedly lowered and raised him over the flames for two hours, in order to make him suffer maximum pain, and in order for the spectacle to reach the desired level of entertainment. As with other lynchings of Black men, pieces of his body were taken as souvenirs. One person ran off with the corpse’s penis. Children cut out his teeth and sold them to the highest bidder.

The mayor and sheriff of Waco watched the proceedings, implying their blessing on the ordeal. The town must cleanse itself of wickedness and throw its sacrificial animal into the fire, in order to protect Lady Liberty, to protect civilization, to defend everything upon which the light of reason and holiness stands.

One might ask how these people slept at night, but they wouldn’t have understood the question in the first place. How could they not sleep at night? They had the law on their side, strength in numbers on their side, strength in technology on their side, strength in economic and political power on their side, strength of God himself on their side. They were doing the dirty work in defending all that is righteous and decent in human civilization, and for this they ought to sleep better than anyone else. The blood on their hands was spilled from holy actions, and if you don’t understand that, then you just don’t understand their way of life.

From their perspective, the lynch mobs of America also had science on their side.

In further effort to justify white supremacy, as well as global European and American imperialism, pseudoscientists at the St. Louis Fair continued showcasing the supposedly God-ordained and Darwin-approved superiority of the white race over darker skinned savages through various ‘living exhibits’ featuring Indigenous peoples from around the globe in what amounted to zoo displays. This was more of the same, a pattern repeated throughout world’s fairs from their inception.

Ota Benga, the famous African Pygmy who was touted as the official ‘missing link’ between apes and human beings, was displayed in St. Louis. It was following his display here that the Bronx Zoo took interest and took him into their oppressive clutch.

Indigenous Filipino people, recently taken under the wing of American imperialism, were also put on display. The eagle of American civilization stood over these people, protecting them from the evil Spanish empire, which of course treated Filipino people much the same way as the American empire did – like subhumans not worthy of even basic levels of respect and dignity. Their practice of eating dogs was of particular interest to the Westerners, who viewed it as a barbaric practice, even as they proudly slurped down pounds of ham and bacon, pigs being near equal, if not equal, to dogs in intelligence.

But this time the racist pseudoscientists would take things a step further.

As the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair hosted the first Olympic Games ever held outside Europe, organizers also green lit what they dubbed ‘Anthropology Days,’ in which Indigenous peoples from around the world would participate in athletic competitions, in an effort to study their capacity as humans through sport.

Dr. J.W. McGee, president of the newly established American Anthropological Association, was disappointed in the results, as many of the athletes either didn’t understand the rules, decided to purposely stray from them, or simply didn’t care enough to try. When some of the Indigenous sprinters stopped short of the finish line in order to cross the tape together with their peers, rather than win first place, the organizers assumed they were incompetent as athletes. But something deeper might have been at work, and the anthropologist’s premise that Indigenous people were as individualistic an e as Europeans likely entirely false: the sprinters might not have even desired to defeat their peers, but rather to share the communal bond that would come from finishing the goal together, which stood in direct odds with the value set mythologized through the displays inside the Crystal Palace half a century earlier.

In addition to these racist faux Olympic competitions, the St. Louis World’s Fair also hosted the largest pipe organ ever assembled, which the New York Times reported “is a church itself in size… as large as a four-story dwelling house, 30 feet wide and 63 feet long.” Inside this massive structure, one could become “almost lost in the maze of stairways, ladders, pipes and bellows.” Some of its pipes were 50 feet long and weighed 1,5000 pounds. Its stops, however, were still sized for human hands.

Watching over the organ and the fair’s racist, imperialistic festivities, sat the companion piece – a bronze eagle weighing in at 2,500 pound by itself. The project cost what today would translate to roughly $3 million, a cost that went over the projected budget by roughly $1 million in today’s currency, a cost that bankrupted its own patron, the Los Angeles Art Organ Company.

What came to be known as the Wanamaker Organ belted out its first earth-rattling vibrations, “causing little thrills to creep up and down the spines of the listeners,” as reported by the New York Times, at the exact moment in 1904 that King George V was crowned in England.

The tensions in Europe which led to World War 1 were brewing.

Fifteen years later, shortly after ‘the war to end all wars’ had finally come to a halt, in its new home inside a popular department store in Philadelphia, the organ delivered its messages of hope and beauty in the first of many popular ‘musician’s assemblies.’ The bronze eagle remained locked in its gaze upon the organ, and its stops, while the people of Omaha read news story after salacious news story, almost all of them false, about ‘Black beasts’ ravaging white women of the city. At the same time, doughboys fresh from the trenches came home to cities into which Black people from the South had flooded in search for a better life, working jobs the white veterans felt belonged to them. Black soldiers returned home to a nation of white supremacists who hated them more than ever. Soldier of all races struggled with PTSD and miserable employment opportunities.

The confusion of World War 1 had made its mark on the world’s psyche, and that trauma had returned to the New World. White vets sought and found a convenient scapegoat onto which they could unleash their terrified, confused, privileged rage and fury.

The war in Europe was over, but tension in the streets of Omaha was beginning to boil as it never had before…